Lord have mercy! The Atlantic just dropped the article of the year, at least as far as this website is concerned. Underneath the slightly been-there-done-that title of “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?” lies an exploration of identity creation and loneliness and self-immolation that may even jerk a few tears of grief. Stephen Marche has crafted a tour-de-force, combing the research, polling the experts and injecting a fair amount of his own considerable insight to form a fairly significant statement about modern life (not to mention a timely endorsement of online communities needing flesh-and-blood get-togethers every once and a while…).

Lord have mercy! The Atlantic just dropped the article of the year, at least as far as this website is concerned. Underneath the slightly been-there-done-that title of “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?” lies an exploration of identity creation and loneliness and self-immolation that may even jerk a few tears of grief. Stephen Marche has crafted a tour-de-force, combing the research, polling the experts and injecting a fair amount of his own considerable insight to form a fairly significant statement about modern life (not to mention a timely endorsement of online communities needing flesh-and-blood get-togethers every once and a while…).

The basic findings will not be surprising to many of you: social media is making us lonelier and unhappier, not because it has some unique power in and of itself, but because it appeals so successfully to the human drive toward self-reliance/-justification, what we might simply describe as “original sin.” He calls it the “compulsion to assert our own happiness” which strikes me as a pretty brilliant distillation. In some cases, social media appears to have eliminated any of the non-performance-related or safe corners of life – when we live 24/7 in the public eye, the judgment of the audience (external and internal) is equally non-stop, and exhaustion, depression and isolation are the chief byproducts. But then there’s the Romans 7 kicker – we know that social media has this effect on/power over us, and yet we choose to engage it anyway. Marche wisely points out that this is not an innovation of the past ten years, it’s simply something fundamental about our nature that’s been amplified by technology.

Morever, Marche uncovers an unavoidable truth: the more we think about ourselves, or the more we focus on our own fulfillment, the less happy we become. Happiness, as they say, cannot be approached directly. Or in theological terms, the only true measure of sanctification is the decreased obsession with measuring one’s sanctification (self-forgetfulness) – which is unfortunately not something that can be achieved through exertion or effort or even education. It is a gift.

This, of course, is where Christianity has such an important piece to add, or you might say, where the Holy Spirit comes in. David Browder reminds us in his wonderful post about Father and Sons, “You cannot be left to create your own identity in a world this big and mean… You need the arm of a father around your neck. In theological language, you must passively receive your identity rather than actively create it.” Amen.

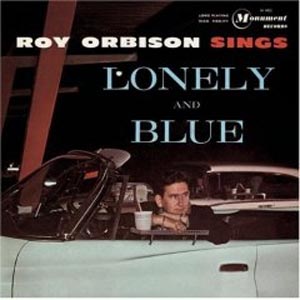

And lest we dismiss this all as some sociological or theological contrivance, Marche is right to invoke the memory of Yvette Vickers, the B-Movie star whose mummified remains were discovered last August, after a year of lying undisturbed in her home. Original sin is a matter of life and death, just as it always has been:

Vickers’s web of connections had grown broader but shallower, as has happened for many of us. We are living in an isolation that would have been unimaginable to our ancestors, and yet we have never been more accessible… We have never been more detached from one another, or lonelier. In a world consumed by ever more novel modes of socializing, we have less and less actual society. We live in an accelerating contradiction: the more connected we become, the lonelier we are. We were promised a global village; instead we inhabit the drab cul-de-sacs and endless freeways of a vast suburb of information.

The new studies on loneliness are beginning to yield some surprising preliminary findings about its mechanisms. Almost every factor that one might assume affects loneliness does so only some of the time, and only under certain circumstances. People who are married are less lonely than single people, one journal article suggests, but only if their spouses are confidants. If one’s spouse is not a confidant, marriage may not decrease loneliness. A belief in God might help, or it might not, as a 1990 German study comparing levels of religious feeling and levels of loneliness discovered. Active believers who saw God as abstract and helpful rather than as a wrathful, immediate presence were less lonely. “The mere belief in God,” the researchers concluded, “was relatively independent of loneliness.”

But it is clear that social interaction matters. Loneliness and being alone are not the same thing, but both are on the rise. We meet fewer people. We gather less. And when we gather, our bonds are less meaningful and less easy.

The ultimate American icon is the astronaut: Who is more heroic, or more alone? The price of self-determination and self-reliance has often been loneliness. But Americans have always been willing to pay that price.

Today, the one common feature in American secular culture is its celebration of the self that breaks away from the constrictions of the family and the state, and, in its greatest expressions, from all limits entirely.

“Facebook can be terrific, if we use it properly,” Cacioppo continues. “It’s like a car. You can drive it to pick up your friends. Or you can drive alone.” But hasn’t the car increased loneliness? If cars created the suburbs, surely they also created isolation. “That’s because of how we use cars,” Cacioppo replies. “How we use these technologies can lead to more integration, rather than more isolation.” The problem, then, is that we invite loneliness, even though it makes us miserable.

Loneliness is certainly not something that Facebook or Twitter or any of the lesser forms of social media is doing to us. We are doing it to ourselves. Casting technology as some vague, impersonal spirit of history forcing our actions is a weak excuse. We make decisions about how we use our machines, not the other way around. Every time I shop at my local grocery store, I am faced with a choice. I can buy my groceries from a human being or from a machine. I always, without exception, choose the machine. It’s faster and more efficient, I tell myself, but the truth is that I prefer not having to wait with the other customers who are lined up alongside the conveyor belt: the hipster mom who disapproves of my high-carbon-footprint pineapple; the lady who tenses to the point of tears while she waits to see if the gods of the credit-card machine will accept or decline; the old man whose clumsy feebleness requires a patience that I don’t possess. Much better to bypass the whole circus and just ring up the groceries myself.

But the price of this smooth sociability is a constant compulsion to assert one’s own happiness, one’s own fulfillment. Not only must we contend with the social bounty of others; we must foster the appearance of our own social bounty. Being happy all the time, pretending to be happy, actually attempting to be happy—it’s exhausting.

Most goals in life show a direct correlation between valuation and achievement. Studies have found, for example, that students who value good grades tend to have higher grades than those who don’t value them. Happiness is an exception. The study came to a disturbing conclusion:

Valuing happiness is not necessarily linked to greater happiness. In fact, under certain conditions, the opposite is true. Under conditions of low (but not high) life stress, the more people valued happiness, the lower were their hedonic balance, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction, and the higher their depression symptoms.

The more you try to be happy, the less happy you are. Sophocles made roughly the same point…

Rising narcissism isn’t so much a trend as the trend behind all other trends. In preparation for the 2013 edition of its diagnostic manual, the psychiatric profession is currently struggling to update its definition of narcissistic personality disorder. Still, generally speaking, practitioners agree that narcissism manifests in patterns of fantastic grandiosity, craving for attention, and lack of empathy. In a 2008 survey, 35,000 American respondents were asked if they had ever had certain symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder. Among people older than 65, 3 percent reported symptoms. Among people in their 20s, the proportion was nearly 10 percent. Across all age groups, one in 16 Americans has experienced some symptoms of NPD. And loneliness and narcissism are intimately connected: a longitudinal study of Swedish women demonstrated a strong link between levels of narcissism in youth and levels of loneliness in old age. The connection is fundamental. Narcissism is the flip side of loneliness, and either condition is a fighting retreat from the messy reality of other people.

Facebook never takes a break. We never take a break. Human beings have always created elaborate acts of self-presentation. But not all the time, not every morning, before we even pour a cup of coffee. Yvette Vickers’s computer was on when she died.

Nostalgia for the good old days of disconnection would not just be pointless, it would be hypocritical and ungrateful. But the very magic of the new machines, the efficiency and elegance with which they serve us, obscures what isn’t being served: everything that matters. What Facebook has revealed about human nature—and this is not a minor revelation—is that a connection is not the same thing as a bond, and that instant and total connection is no salvation, no ticket to a happier, better world or a more liberated version of humanity. Solitude used to be good for self-reflection and self-reinvention. But now we are left thinking about who we are all the time, without ever really thinking about who we are. Facebook denies us a pleasure whose profundity we had underestimated: the chance to forget about ourselves for a while, the chance to disconnect.